It was December 1996 and my father had just bought a copy of John le Carré’s newly published spy thriller, The Tailor Of Panama. When he saw that the book’s hero had almost the same surname as him, he smiled.

But the further he read, the more the coincidences began to pile up, and by the time he’d reached the end, he was astonished. This wasn’t a fictional spy tale, he told himself. This was the story of his own father’s life.

Dad was amazed but also angry. He had known that his father worked for the Secret Intelligence Services, also known as MI6, in the Second World War, but when he had tried to get hold of a copy of his file, he’d been told it didn’t exist.

Le Carré, too, had been a spy, working for both MI5 and MI6, a training in the serious business of espionage that featured heavily in last week’s obituaries of the author, who died eight days ago aged 89.

Had le Carré gained access to my grandfather’s papers and plundered them for his book? There didn’t seem to be any doubt about it. My father shot off a letter to the publishers demanding a ‘full and immediate explanation’.

He didn’t have to wait long for an answer.

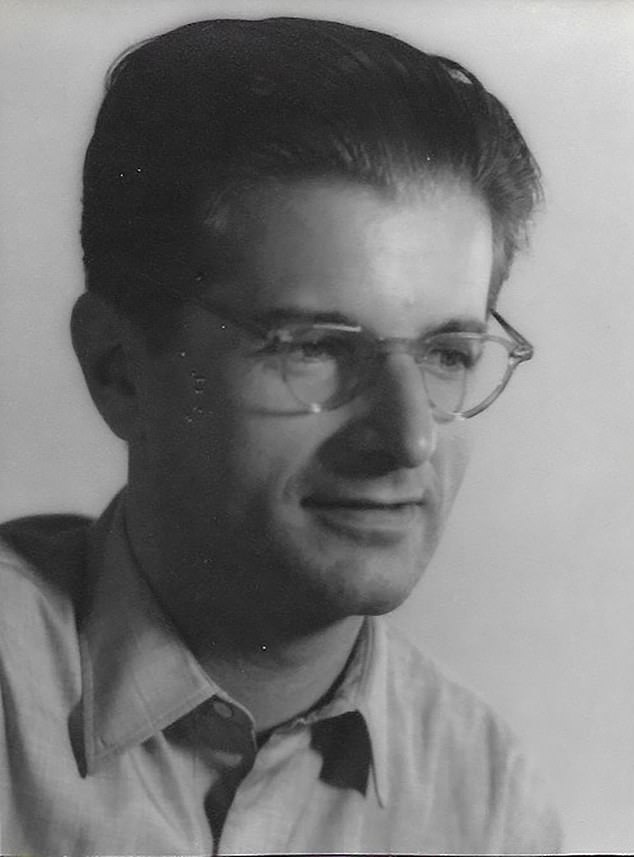

It was December 1996 and my father had just bought a copy of John le Carré’s newly published spy thriller, The Tailor Of Panama. Pictured is George Pendle

The Tailor Of Panama sat atop the best-seller lists for months. Many ranked it alongside le Carré’s greatest works such as The Spy Who Came In From The Cold and Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy. Although, this time, le Carré’s more familiar post-war settings – rain-sodden London and the frozen forests of Mitteleuropa – made way for the tropical heat of Central America.

Harry Pendel, the main character, has a successful tailoring business in Panama City, but he is also a former convict and a teller of tall tales, and much of his past life is an invention of his own making. When an Old Etonian MI6 agent named Andy Osnard uncovers the truth about his past, and the fact he’s in great debt, he offers both discretion and financial help if Pendel agrees to supply intelligence to London.

The tailor agrees, but the information he supplies about an impending revolution is largely fictitious. However, soon his imaginary life begins to become all too real. People start dying. Eventually, the British and American governments use his lies to justify an invasion.

The book also spawned an acclaimed 2001 film starring Oscar-winner Geoffrey Rush as Harry Pendel, and the former James Bond, Pierce Brosnan, as Osnard.

My Grandad had never been a criminal fantasist like Harry Pendel but he was almost certainly a spy. Harry Pendel had lived in Panama. My grandfather, George Pendle, had lived in Paraguay. Harry Pendel had run a tailoring business named Pendel & Braithwaite, known as P&B. George Pendle had run a textile business named Pendle & Rivett, known as P&R. Harry Pendel was on close terms with Panamanian government ministers. George Pendle was on close terms with Paraguayan government ministers.

Both Pendel and Pendle were British expats who had married Latin American wives with exotic sisters who both owned bankrupt farms they had been forced to sell. And most tellingly of all, Pendel and Pendle had both been recruited by Old Etonians to work as spies for the Secret Intelligence Service. The specific similarities were so numerous they surely defied mere coincidence.

By the end of his life – he died in 1977 – my grandfather had become a respected author and broadcaster on South America. But there was a time in the late 1930s and early 1940s, as war raged in Europe, when his activities were cloaked in mystery and remained so, even to his family.

So far as they could establish, he had been recruited into the secret service in London by the future British Ambassador to Uruguay, Sir Eugen Millington-Drake, an Old Etonian. Fluent in Spanish and German, my grandad had been ordered to Paraguay under cover of being a member of the British Council and to work his way into the confidence of a colony of Germans living in the country. This included several political and military newcomers.

But how was he to do it?

The Tailor Of Panama sat atop the best-seller lists for months. Harry Pendel, the main character, (pictured) has a successful tailoring business in Panama City, but he is also a former convict and a teller of tall tales, and much of his past life is an invention of his own making

The story was that he was staying in a hotel in the Paraguayan capital of Asuncion where many Germans lived, when he noticed that one had a pet monkey that liked to steal shiny objects.

He laid his pocket watch on his windowsill where the monkey could easily see it. As planned, the pet stole the watch, allowing my grandfather to go to its owner’s room and politely enquire about its return. An easy friendship with the German followed.

Through his new friend, and his connections, my grandfather was rumoured to have discovered crucial information about German naval plans in the region, including the whereabouts of the German pocket battleship Admiral Graf Spee which was roving the Atlantic sinking Allied merchant ships.

This led directly to the Battle of the River Plate, the first naval battle of the Second World War, in which Graf Spee was destroyed. It was a massive Allied victory, and my family were certain my grandfather had played a crucial part.

But where was the proof? All we had were the whispers and a signed photograph of Millington-Drake inscribed: ‘To Pendle of Paraguay.’

Two days after my father wrote his letter to le Carré’s publishers, he received an eight-page reply from the author himself. It had been sent from his clifftop home in Cornwall, and was written on paper headed with the novelist’s real name, David Cornwell.

It was clear that my father’s letter had given the author a shock. ‘I was as astonished and distressed by your letter as you appear to be by my novel,’ he wrote. He said that he had immediately thought my father’s letter was a hoax or a con, but couldn’t work out what the angle could possibly be.

The grand Buckinghamshire property owned by George Pendle that le Carré would pass in the 1960s

So, assuming my father was telling the truth, he went on to write: ‘I sincerely ask you to accept that I, too, am telling the absolute truth: I never heard of your father… Harry Pendel is entirely a creature of my own imagination.’

Le Carré wrote that it was true he had worked for British intelligence, and so we might think that my grandfather’s story had ‘somehow filtered through’ to him. But he then declared that to be ‘impossible’ since his work with MI6 had no connection with the Americas and ‘information did not spill over from one regional section to another’.

He also wrote that because my grandfather’s service took place long before his own career, it couldn’t possibly have had any relevance to anything that was crossing his desk during his time in the secret service.

He conceded that the remaining similarities were enough to leave him ‘appalled’ and would be ‘circumstantially, unanswerable in court’, but insisted that they were ‘coincidences of extraordinary dimensions’.

He went on to explain that if he had knowingly used my grandfather’s story, he would have had to lie to his solicitor, lie to his publishers, break the Official Secrets Act and ‘risk the wrath of my former masters’.

Most persuasively, he suggested that if he had borrowed the story, ‘the least I would have done, surely, was change your father’s name more radically than merely rearranging the last two letters!’

Was le Carré, the master of dissimulation, which his obituarists said was almost second nature, telling the truth in this instance? His biographer, Adam Sisman, who knew him perhaps as well as anyone could, thinks he was.

‘I’m used to David’s deceptions, of which there are many,’ he tells me. ‘And that letter has the ring of sincerity to me. I think that he was genuinely amazed.’

Sisman says that le Carré drew his plots and characters from all over the place, and would then stitch them together. For instance, his famous, dogged spymaster George Smiley was a blend of both his former MI5 colleague John Bingham, from whom he ‘borrowed’ many specific small gestures – such as polishing his spectacles on the end of his tie – and his former university tutor, Vivian Green, from whom he took Smiley’s character.

However, there was another incident which makes the link between le Carré’s Pendel and my grandfather so plausible.

When an intelligence officer named David Smiley approached le Carré and asked him whether he had used his name for his spy – his sons had gone to Eton around the time le Carré was a teacher there – the author could not provide a definite answer. ‘Maybe I did pinch your name from the school list, but it would only have been unconsciously.’ If he did, he didn’t even change the last two letters.

According to Sisman, many people have seen themselves in le Carré’s books, but it is significant that in all his years of writing the only person to seriously threaten to sue the author for using their story without permission was his own father, Ronnie Cornwell, a conman, who haunts many of le Carré’s novels in one guise or another.

My father was naturally disappointed by le Carré’s letter. The Tailor Of Panama had seemed to open a door on his father’s secretive past – only for le Carré to slam it shut. Faced with such a forceful denial, the correspondence ended. My father passed away two years ago, still not knowing the truth.

Perhaps it really was an extraordinary coincidence, as le Carré insisted. But there was something in the force of his rebuttal that never quite sat right with our family.

Le Carré himself had always sent mixed messages about a writer’s relationship with the truth. When The Tailor Of Panama was published, he said: ‘Anybody in the creative business… has some sense of guilt about fooling around with fact, that you’re committing larceny, that all of life is material for your fabulations. That was certainly Harry Pendel’s position.’

Was it le Carré’s, too?

Shortly after his death, Radio 4 replayed one of his interviews.

In it, the author spoke of how, in the early 1960s, he lived in Great Missenden, Buckinghamshire. Each morning, he recalled, he would walk down the hill to the railway station and conjure up his first spy novels on the train in to London on his way to work at MI5.

Now it was my turn to be startled. For there was a grand house at the top of that hill named Bocken, which he would have passed every day.

It was, at that time, the family home of my grandfather, George Pendle.